Yes, there were, and it’s unlikely we’ll ever be able to name them all, but we would like to name the ones we can in an effort to honor their existence and to recognize the wrong done them with their enslavement.

In 1716 Major John Freeman, a large landowner in what is today Brewster, provided in his will ‘freedom for my negroes,” leaving each four acres, a horse, and a cow, and further charging that “I desire my children to put them in such way as they may not want.”

In 1729 Kenelm Winslow’s estate inventory lists a “negro man named Caesar” and his wife and two children, valued at 130 pounds.

That same year Samuel Hall bequeathed his wife Patience [later the second wife of the below-mentioned Thomas Clark] an unnamed “old negro man” and “negro girl.”

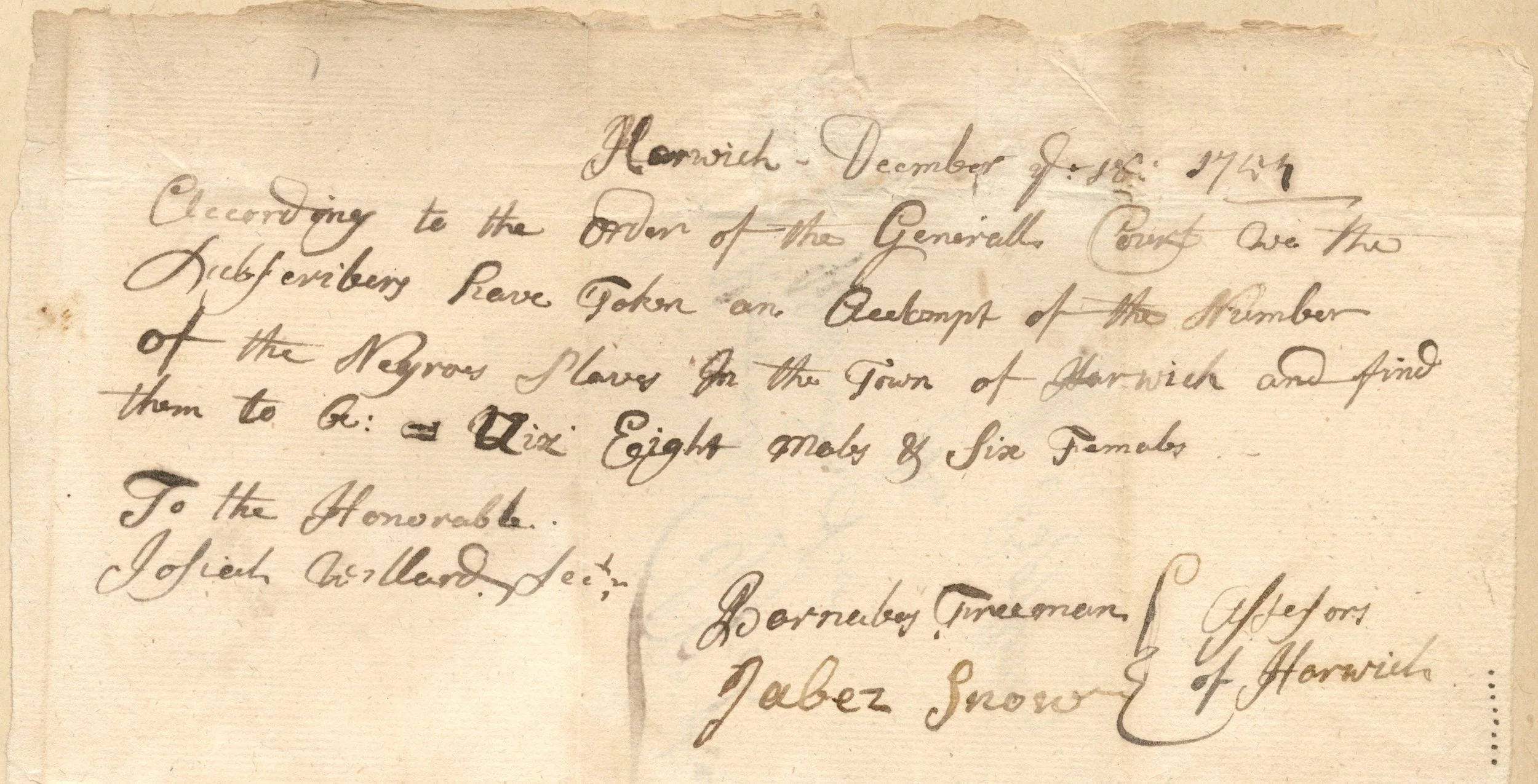

The 1754 “Enumeration of Slaves” for the town of Harwich, which until the 1803 separation included today’s Brewster, records eight male and six female slaves.

ENUMERATION OF SLAVES 1754

According to the Order of the General Court we the subscribers have taken an account of the number of the Negroes [sic] Slaves in the Town of Harwich [in 1754 this included Brewster] and find them to be Viz: Eight males and Six females

To the Honorable

Josiah Willard, Sec’try

[signed] Barnaby Freeman

Jabez Snow

(Assessors of Harwich)

A 1755 will written by Thomas Clark, who lived near the grist mill on Stony Brook Road, deeded to his first wife Sarah his “little slave Molly.”

BILL OF SALE SLAVE MOLLY

…I also give unto my wife my little slave Molly…

Benjamin Bangs, whaleman, trader, and diarist, who lived across the street from First Parish Meeting House, recorded in his diary:

December 3, 1747: “Silas Negro given to me this day.”

February 29, 1760: “I had Sarah Negro come here to live. I bought her at 200 pounds old Ten[or].”

December 15, 1760: “I sold my Negro Oliver and very glad to get rid of him for Thirty Nine pounds Law’l Mony to Eleazer Nickerson Bass ponds . . .”

February 19, 1762: “I sold old Amos and Jesse this day.”

Below is the bill of sale for Sarah, purchased for twenty-six pounds thirteen shillings. She had contracted a form of tuberculosis called The King’s Evil, believed to be cured by the touch of royalty. Sarah was sold with a warranty of sorts -- if the disease returned, Bangs’ money would be refunded:

BILL OF SALE SLAVE SARAH

Harwich March 1760

Receiv’d of Benj’n Bangs Twenty-five pounds thirteen shillings and four pence in full Equally between us [illegible] For a Negro Woman Names Sarah Which formerly [belonged?] to Thomas Clark Esq. and his wife Mrs. Patience Clark both deceas’d for consideration whereof we do thereby sell and warrant the said Negro Woman to the said Bangs and his heirs during her life against the claims of any person whatsoever. In witness whereof we [Illegible] set our hand this Eleventh Day of March Anno Domini 1760

Thomas Clark

Seth Clark

In presence of

Roger King

Ebenezer Allen

Harwich March 11th 1760

Whereas we the subscribers having this day sold a negro woman names Sarah to Benj’n Bangs and He has paid us in full and the said negro having some time ago had the King’s Evill [a form of tuberculosis believed cured by the touch of royalty] which is judged now to be cured But in case the said negro should not be cured or have the said distemper upon her within two years from the date as may be judged to be By a Doctor so as to be to the damage of said Bangs we hereby promise to return the sum of 26=13=4 law’l money or to make the damage good as we shall agree witness our hand

In presence of

Roger King

Ebenezer Allen

Thomas Clark

Seth Clark

At the time of Bangs’s death in 1769 his estate inventory listed one unnamed slave.

A 1771 Massachusetts tax inventory lists Brewster residents Joseph Wing, Desire Bangs (Benjamin’s widow), Kenelm Winslow, Nathaniel Stone, and Elkanah Bangs as possessing “servants for life.” Research on this term is ongoing, but in Exodus 21 reference is made to an enslaved person who is offered freedom but chooses to stay with his master and “serve for life.” Often this decision was made because the rest of the family was still enslaved.

In 1781 Kenelm Winslow bequeathed his wife Abigail “my Negro.”

And then came Elizabeth Freeman. Known in later life as “Mum Bett,” she had nothing to do with Brewster other than the fact that she impacted the lives of every enslaved person in Massachusetts. Enslaved since infancy, she ran away at the age of forty, after her mistress attempted to hit her sister with a heated shovel and hit Mum Bett instead.

Mum Bett’s enslaver, John Ashley of Sheffield, MA, applied to the law for her return, but Mum Bett got a lawyer of her own. Her husband had died fighting in the Revolutionary War, and she’d listened closely to the political talk around the Ashley table. She’d heard about the Bill of Rights and the new state constitution and decided that if all people were born free and equal, then the law must apply to her, too.

Mum Bett enlisted the help of an attorney named Theodore Sedgewick, whose anti-slavery sentiments were well known. Sedgewick won the case in county court, making Mum Bett the first enslaved African American to be freed under the Massachusetts constitution of 1780. This municipal case set a precedent that was affirmed by the state courts in the Quock Walker case in 1783, which ultimately led to the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts.

Mum Bett enlisted the help of an attorney named Theodore Sedgewick, whose anti-slavery sentiments were well known. Sedgewick won the case in county court, making Mum Bett the first enslaved African American to be freed under the Massachusetts constitution of 1780. This municipal case set a precedent that was affirmed by the state courts in the Quock Walker case in 1783, which ultimately led to the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts.

The 1790 census lists no slaves in Brewster.

Although to date no studies have unearthed direct evidence that any of Brewster shipmasters traded in slaves, research is ongoing, and if more evidence becomes known, it will be included in our narrative. On the other hand, there is ample evidence that all benefited financially by trade associated with that institution. Here is one basic example: Alewives from Brewster’s herring run on Stony Brook Road were caught, salted, packed in barrels, shipped to Boston, and on to the West Indies to feed the enslaved on the sugar cane plantations. Consider who benefited financially from this small-scale, peripheral connection to the slave trade: The fishermen who caught the fish, the men who made their nets, the men who delivered the salt to preserve the alewives, the coastal traders who delivered the barrel staves to the local coopers who made the barrels, and last of all the sea captains who delivered the alewives to Boston and then on to the West Indies.